When Eliza Runs Away From Mr. Shelby

| |

| Writer | Harriet Beecher Stowe |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Hammatt Billings (1st edition) |

| Country | Us |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publication engagement | March 20, 1852 |

| Media blazon | Print (Hardback and Paperback) |

| OCLC | 950905879 |

| Followed by | A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853) |

Uncle Tom'due south Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel past Harriet Beecher Stowe. Information technology was published in 1852. It greatly influenced many people'southward thoughts almost African Americans and slavery in the U.s.a.. It also strengthened the disharmonize between the Northern and Southern United states of america. This led to the American Ceremonious War. The book'due south effect was and so powerful that Lincoln said when he met Stowe at the beginning of the Civil War, "So this is the fiddling lady who made this big state of war."[one] [2]

The main character of the novel is Uncle Tom, a patiente sentimental novel showed the effects of slavery. It also said that Christian dear is stronger than slavery.[3] [iv]

Uncle Tom's Cabin was the most popular novel of the 19th century,[5] and the second best-selling book of the century (the first one was the Bible).[half-dozen] It helped abolitionism spread in the 1850s.[7]

In these days, it has been praised every bit a very important help to anti-slavery. Nonetheless, it has also been criticized for making stereotypes about black people.[8] [9] [10]

Inspiration and references [change | change source]

Harriet Beecher Stowe was born in Connecticut. She was an abolitionist. Stowe wrote her novel because of the 1850 passage of the 2d Fugitive Slave Act. This law punished people who helped slaves run abroad. It too made the North cease and return the S's black runaways. Mrs. Edward Beecher wrote to Harriet ("Hattie"), "If I could use a pen as you lot tin, I would write something that will make this whole nation experience what an accursed thing slavery is."[11] At that fourth dimension, Stowe was a wife with six children who sometimes wrote for magazines.[11] Her son, Charles Stowe, said that his mother read this letter out loud to her children.[eleven] When she finished the letter, she stood up, and with "an expression on her face that stamped itself on the heed of her child",[11] she said, "I will write something...I will if I live."[ii] [11] That is how Uncle Tom's Cabin began.

Co-ordinate to Stowe, she began thinking about Uncle Tom'southward Cabin; or, Life Amid the Lowly equally she was in a church in February 1851.[2] She had a vision of a Christian black man being beaten and praying for the people who were beating him equally he died.[2] She was likewise partly inspired to write her novel by the autobiography of Josiah Henson. Henson was a blackness man who had run away and helped many blackness slaves.[12] She was also helped by the book American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thou Witnesses by Theodore Dwight Weld and the Grimké sisters.[13] Stowe also said that she got lots of ideas for Uncle Tom'due south Cabin by talking to runaway slaves when she was living in Cincinnati, Ohio.

In her book A Fundamental to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853), Stowe wrote about the stories that inspired her when she was writing Uncle Tom's Cabin.[14] Nevertheless, afterwards research showed that Stowe did not actually read many of the stories inside the book until after her novel was published.[14]

Publication [change | modify source]

Uncle Tom's Motel began in a series in an anti-slavery newspaper, The National Era. The National Era had also printed other works Stowe had written. Because everybody liked the story so much, John P. Jewett of Boston asked Stowe to plough the series into a book. Stowe was not certain if people would like to read the story as a volume. However, she finally agreed. John Jewett, sure that the book would exist popular, asked Hammatt Billings to engrave six pictures for the book.[xv] In March twenty, 1852, the finished book came out.[2] By June information technology was selling ten yard copies a week. By October American sales alone were 150 thousand copies.[ii] In the beginning year it was published, 300,000 copies of the volume were sold, and it was translated into many important languages.

Summary [alter | change source]

Eliza's escape, Tom is sold [change | change source]

A Kentucky farmer named Arthur Shelby is afraid of losing his subcontract because of debts. Even though he and his wife, Emily Shelby, are kind to their slaves, he decides to sell two of them: Uncle Tom, a center-aged homo with a wife and children, and Harry, the son of his wife's maid Eliza. Emily Shelby is shocked and unhappy considering she promised Eliza that she would not sell her son. George Shelby, her son, is unhappy considering he admires Uncle Tom every bit his friend and Christian.

When Eliza hears about Mr. Shelby's plans to sell her son, she decides to run away with her but son. She writes a letter saying sorry to Mrs. Shelby and runs away that night.

Meanwhile, Uncle Tom is sold and put into a boat, which sails down the Mississippi River. There, he makes friends with a girl called Evangeline ("Eva"). When Eva falls into the water and he saves her, Eva's male parent, Augustine St. Clare, buys Tom. Eva and Tom become good friends considering they both dear Jesus very deeply.

Eliza'southward family hunted, Tom'southward life with St. Clare [change | change source]

During Eliza's escape, she meets her hubby, George Harris, who had run away earlier her. They decide to endeavor to run away to Canada. All the same, they are hunted by a slave hunter named Tom Loker. Tom Loker finally traps Eliza and her family, so that George shoots Loker. Eliza is worried that Loker might die and get to hell. Because of this, she persuades her husband to take him to a Quaker town to get better. The gentle Quakers change Tom Loker greatly.

In St. Clare'southward house, St. Clare argues with his sis, Miss Ophelia. She thinks that slavery is wrong, but is prejudiced confronting blacks. St. Clare buys Topsy, a black child, and challenges Miss Ophelia to educate her. Miss Ophelia tries, but fails.

After Tom has lived with St. Clare for well-nigh 2 years, Eva becomes very sick. She has a vision of sky before she dies. Because of her death, many people alter. Miss Ophelia loses her prejudice of black people, Tospy decides to go "adept", and St. Clare decides to free Tom.

Tom'due south life with Simon Legree [change | modify source]

St. Clare, nevertheless, is hurt when he tries to stop a fight at a tavern and dies. Considering of this, he cannot keep his promise to free Tom. His married woman sells Tom to a plantation owner named Simon Legree. Legree takes Tom to Louisiana. In that location, he meets other slaves, including Emmeline (who Legree bought at the same time that he bought Tom). Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom disobeys his social club to whip the other slaves. Legree beats him, and decides to destroy Tom's organized religion in God. Still, Tom secretly continues to read the Bible and aid the other slaves. At the plantation, Tom meets Cassy, some other black slave. Her 2 children had been sold, and she had killed her third child because she was agape that her child would exist sold, likewise.

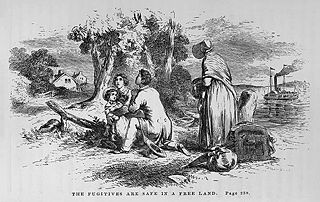

Loker has been changed because of the Quakers. George, Eliza, and Harry have finally reached Canada and get free. Meanwhile, Uncle Tom feels so unhappy that he almost gives up, just he has 2 visions of Jesus and Eva. He decides to continue to be a Christian, even if he has to die. Cassy and Emmeline, with Tom'south encouragement, run away. They cleverly use Legree's superstitious fears to assistance them. When Tom does not tell Legree where they are, Legree tells his men to beat him to death. Tom forgives the 2 men who beat him equally he dies, and they feel sorry and become Christians. George Shelby comes just as Tom is dying to free him. He is very angry and sad. Even so, Tom, saying smilingly, "Who,—who,—who shall divide us from the dear of Christ?" dies.[xvi]

Important characters [change | change source]

Uncle Tom [change | change source]

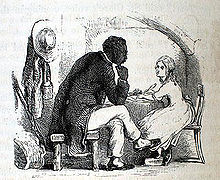

Fullpage illustration by Hammatt Billings for Uncle Tom's Cabin (First Edition: Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1852). Cassy helps Tom afterward he is beaten by Simon Legree.

Uncle Tom, the title character of the story, is a patient, noble, unselfish blackness slave. Stowe wanted him to be a "noble hero": in the book, he stands up for what he believes in. Even though they do non want to, even his enemies admire him.[17]

Recently, however, his proper name has also been used negatively. People often recollect of "Uncle Tom" as an old black human trying to make his masters happy, every bit people have criticized his repose credence of slavery.[18] However, others argue that this is not true. Beginning of all, Uncle Tom is not actually old - he is only 8 years older than Mr. Shelby, which shows that he is probably effectually fifty.[ix] [18] Also, Tom is non happy with slavery.[18] His acceptance is not because of stupidity or because he likes slavery. It is because of his religious faith, which tells him to dearest everyone. Wherever Uncle Tom goes, he loves and spreads comfort and kindness. He helps slaves escape, such every bit Eliza, Emmeline and Cassy. He also refuses to beat other slaves. Because of this, he is browbeaten himself. Stowe was not trying to make Tom an example for blacks but for white and black people.[18] She says that if white people were to be loving and unselfish like Uncle Tom, slavery would be impossible.[18]

Eliza Harris [alter | modify source]

Eliza Harris is Mrs. Shelby'southward favorite maid, George Harris' wife, and Harry'due south mother. Eliza is a dauntless, intelligent, and very beautiful young slave. Eliza loves her son, Harry, very much. It is possible her love for him was even greater because she lost ii of her first babe children. Her motherly love is shown when she bravely escapes with her son. Perhaps the most well-known function of Uncle Tom's Motel is the part where Eliza escapes on the Ohio River with Harry.

This escape is said to have been inspired by a story heard in the Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati past John Rankin to Stowe'southward husband Calvin, a professor at the schoolhouse. In Rankin's story, in February, 1838, a immature slave woman had escaped across the frozen Ohio River to the town of Ripley, Ohio with her child in her arms and stayed at his business firm earlier she had gone further towards the north.[xix]

Eva [change | change source]

Picture of Tom and Eva by Hammatt Billings for the 1853 edition of Uncle Tom's Motel.

Eva "Evangeline" St. Clare is St. Clare and Marie'due south celestial daughter. She enters the story when Tom saves her from drowning when he was going to be sold. Eva asks her father to buy Tom. She says, "I want to brand him happy".[16] Through her, Tom becomes St. Clare's leading coachman and Eva'due south "especial attendant (helper)...Tom had...orders to let everything else go, and attend to Miss Eva whenever she wanted him,—orders which our readers may fancy (imagine) were far from bellicose to him."[sixteen] She is very beautiful: "Her form was the perfection of childish beauty...Her face was remarkable less for its perfect beauty of features than for a singular (foreign) and dreamy earnestness (seriousness) of expression...all marked her out (made her different) from the other children, and made every one turn and look later her".[16]

To Tom, she "...seemed something almost divine; and whenever her gold head and deep blue eyes peered (looked) out upon him...he half believed that he saw one of the angels stepped out of his New Attestation."[16] He says that "She's got the Lord's mark in her forehead."[16] Eva is an almost perfect, Christ-like child. She is very sad well-nigh slavery. She does not run across the difference betwixt blacks and whites. She talks very much nearly love and forgiveness. Even Topsy is touched past her love. Eva becomes one of the most important people in Tom'south life.

Ophelia St. Clare [alter | modify source]

"The higher circle in the family...agreed that she was no lady...they were surprised that she should be any relation of the St. Clares...She sewed and stitched abroad, from daylight till dark, with the energy of one who is pressed on by some immediate urgency; so, when the lite faded (went abroad)...out came the ever-ready knitting-piece of work, and at that place she was again, going on as briskly (busily) as always. It really was a labor to see her."[16]

-Uncle Tom's Cabin

Ophelia St. Clare is perhaps the most complicated female character in the novel. St. Clare calls her, "...desperately ... good; it tires me to death to think of it." She does not similar slavery. However, she does not like to be touched or come up close to whatsoever black person as a human. When she first saw Eva "...shaking hands and kissing" with the blacks, she declared that it had "...adequately turned her stomach (fabricated her feel sick)."[xvi] She adds, "I desire to be kind to everybody, and I wouldn't accept anything hurt; but as to kissing...How can she?"[16]

She has a "clear, strong, active heed",[xvi] and is very practical. Still, she has a warm heart, which she shows in her love for St. Clare and Eva. Ophelia hates slavery, simply has a deep prejudice against blacks. St. Clare, equally a challenge to her, buys Topsy. He tells her to endeavour educating her. At first she tries to teach and help Topsy merely because of duty. Nonetheless, Stowe says that duty is not enough: there must be love. Eva'southward death changes Ophelia. When Topsy cries, "She said she loved me...there an't (is non) nobody left now...!"[16] Ophelia gently says, equally "honest tears" fell down her face, "Topsy, you poor child...I tin can love yous, though I am non like that honey picayune kid. I hope I've learnt something of the love of Christ from her. I can love you...and I'll try to aid yous to grow up a good Christian girl."[16] Stowe thought that there were many people like Miss Ophelia St. Clare, who did not like slavery simply could not recall of blacks as people. She wanted to write almost such problems through Miss Ophelia.

Other characters [alter | change source]

- Arthur Shelby, the owner of Uncle Tom in Kentucky, Shelby sells Tom to Mr. Haley to pay his debts. Arthur Shelby is a clever, kind, and basically skilful-hearted man. Notwithstanding, he still does slavery and is not as morally potent as his wife. Stowe used him to show that slavery makes everyone who does it become wicked - non just the cruel masters.

- Emily Shelby is Arthur Shelby'southward loving, gentle, and Christian wife. She thinks slavery is wrong. She tries to persuade her husband to help the Shelby slaves and is i of the many kind female person characters in the story.

- George Shelby is the immature son of Mr. and Mrs. Shelby. Good-hearted, passionate, and loving, he is Uncle Tom's friend. Because of this, he is very aroused when Uncle Tom is sold. After Tom dies, he decides to complimentary all the slaves on the Shelby'due south farm, maxim, "Witness (run into), eternal God! oh, witness, that, from this 60 minutes, I volition exercise what one man tin can to drive out this expletive of slavery from my land!"[16] He is morally stronger than his father. He does what he promises and thinks.

- George Harris Eliza's husband. A very clever and curious mulatto homo, he loves his family unit very much and fights for his freedom bravely and proudly.

- Augustine St. Clare Eva's father. Augustine St. Clare is a romantic, playful man. He does non believe in God, and drinks wine every nighttime. He loves Eva very securely and feels deplorable for his slaves. However, similar Mr. Shelby, he does not practise anything most slavery.

- Marie The wife of St. Clare. She is "...a yellow faded, sickly woman, whose time was divided amid a variety of fanciful diseases, and who considered (thought) herself...the virtually sick-used and suffering person [that lived]..."[16] Silly, complaining, and selfish, she is the opposite of people similar Mrs. Shelby and Mrs. Bird. She thinks slavery is adept and says about Topsy, "If I had my way, now, I'd ship...[her] out, and have her thoroughly whipped; I'd have her whipped till she couldn't stand up!"[16] Later on her husband dies, she sells all the slaves.

- Topsy the "heathenish" black slave girl who Miss Ophelia tries to change. At get-go, Miss Ophelia "...[approaches] her new subject very much as a person might be supposed to approach a black spider, supposing them to have chivalrous (kind) designs toward it".[16] Topsy feels this deviation from duty and love. When Eva says, "Miss Ophelia would dearest y'all, if yous were expert," she laughs and says, "No; she can't bar (carry) me, 'cause I'm a nigger (black)! she'd 's before long take a toad impact her! At that place can't nobody dearest niggers, and niggers tin't exercise nothin' (nothing)! I don't care."[16] Still, in time, she grows to beloved and respect people through Eva'due south love. She later becomes a missionary to Africa.

- When she starting time enters the story, she says that she does non know who made her: "I due south'pect I growed. Don't recall nobody never made me."[16] In the early-to-mid 1900s, some doll companies made dolls that looked like Topsy. The expression "growed like Topsy" (later "grew similar Topsy") began to be used in the English linguistic communication. At first it meant to describe growing without planning it. After, it simply meant growing a lot.[20]

- Simon Legree a slave-owner who cannot intermission Uncle Tom of his Christian faith. He has Uncle Tom whipped to death because of this. He sexually exploits his female slaves Cassy and Emmeline. His name is used as a synonym for a brutal and greedy homo.

Important themes [change | change source]

The moving picture shows George Harris, Eliza, Harry, and Mrs. Smyth subsequently they escape to freedom. By Hammatt Billings for Uncle Tom's Motel, First Edition.

Slavery [change | alter source]

Uncle Tom's Cabin's most of import theme is the evil of slavery.[21] Every part in Uncle Tom'south Cabin develops the characters and the story. But most importantly, it e'er tries to evidence the reader that slavery is evil, un-Christian, and should not be immune.[22] One way Stowe showed the evil of slavery was how it forced families from each other.[23]

Motherhood [change | modify source]

Stowe thought mothers were the "model for all of American life".[24] She also believed that only women could relieve[25] the The states from slavery. Because of this, another very of import theme of Uncle Tom'southward Cabin is the moral power and sanctity of women. White women like Mrs. Bird, St. Clare's mother, Legree's mother, and Mrs. Shelby try to brand their husbands help their slaves. Eva, who is the "ideal Christian",[26] says that blacks and whites are the same. Blackness women like Eliza are dauntless and pious. She escapes from slavery to salvage her son, and by the terminate of the novel, has made her whole family unit come together over again. Some critics said that Stowe'southward female characters are often unrealistic.[27] Nevertheless, Stowe's novel made many people remember "the importance of women's influence" and helped the women's rights movement later.[28]

Christianity [change | change source]

Stowe's puritanical religious beliefs are also 1 of the biggest themes in the novel. She explores what Christianity is like. She believed that the near important thing in Christianity was beloved for everyone. She also believed that Christian theology shows that slavery is wrong.[29] This theme can be seen when Tom urges St. Clare to "look abroad to Jesus" after St. Clare's girl Eva dies. After Tom dies, George Shelby says, "What a thing information technology is to exist a Christian."[30] Because Christian themes are and so of import, and considering Stowe often directly spoke in the novel near religion and organized religion, the novel is written in the "form of a sermon."[31]

Style [alter | change source]

Eliza crossing the icy river, in an 1881 theater poster

Uncle Tom's Cabin is written in a sentimental[32] and melodramatic mode. This style was often used in the 19th century sentimental novel and domestic fiction (as well called women's fiction). These genres were the most popular novels of Stowe's time. It usually had female characters and a mode that fabricated readers feel sympathy and emotion for them.[33] Stowe's novel is different from other sentimental novels considering she writes about a large theme like slavery. Information technology is likewise different because she has a human being (Uncle Tom) as the main character. Yet, she withal tried to make her readers have stiff feelings when they read Uncle Tom's Cabin, like making them weep when Eva died.[34] This kind of writing made readers react powerfully. For example, Georgiana May, a friend of Stowe'due south, wrote a letter to the writer. In the letter, she said that "I was up (awake) last night long after one o'clock, reading and finishing Uncle Tom's Cabin. I could not leave it any more than than I could have left a dying kid."[35] Another reader said that she thought about the book all the time and even idea about changing her daughter'due south name to Eva.[36] The death of Eva afflicted lots of people. In 1852, 300 baby girls in Boston were named Eva.[36]

Even though many readers were very moved, literary critics did non like the style in Uncle Tom's Motel and other sentimental novels. They said these books were written by women and had "women's sloppy (messy) emotions."[37] I literary critic said that if the novel not been about slavery, "information technology would exist just another sentimental novel".[38] Another said the book was a "slice of hack (messy) work."[39] In The Literary History of the U.s., George F. Whicher chosen Uncle Tom's Cabin "Lord's day-school fiction".[twoscore]

Still, in 1985 Jane Tompkins wrote differently about Uncle Tom'due south Motel in her book In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction. [37] Tompkins praised Uncle Tom's Cabin'south fashion. She said that sentimental novels showed how women's emotions inverse the world in a good way. She also said that the pop domestic novels written in the 19th century, like Uncle Tom's Cabin, were intelligently written. She also said that Uncle Tom's Cabin shows a "critique of American society far more devastating (powerful) than whatever ... by ameliorate-known critics such as Hawthorne and Melville."[40]

Reactions to the novel [change | modify source]

Uncle Tom's Cabin has had a very cracking influence. There are not many novels in history that changed guild and so powerfully.[41] When it was published, Uncle Tom's Motel, people who dedicated slavery were very aroused and protested against it. Some people fifty-fifty wrote books against information technology. Abolitionists praised it very much. As a all-time-seller, the novel greatly influenced afterwards protest literature.

Gimmicky and world reaction [modify | modify source]

Equally soon as it was published, Uncle Tom's Cabin fabricated people in the American Southward very aroused.[42] The novel was also greatly criticized by people who supported slavery.

A famous novelist from the South, William Gilmore Simms, said that the book was not truthful.[43] Others called the novel criminal and said information technology was full of lies.[44] A person who sold books in Mobile, Alabama had to leave town for selling the novel.[42] Stowe received threatening letters. She fifty-fifty received a package with a slave's cut ear once.[42] Many Southern writers, like Simms, soon began writing their ain books about slavery.[45]

Some critics said that Stowe had never actually went to a Southern plantation and she did non know much about Southern life. They said that because of this, she fabricated wrong descriptions about the South. Still, Stowe always said she made the characters of her book by stories she was told by slaves that ran away to Cincinnati, Ohio, where she lived. It is reported: "She observed firsthand (herself) several incidents (happenings) which ... [inspired] her to write [the] famous anti-slavery novel. Scenes she observed (saw) on the Ohio River, including seeing a husband and wife being sold apart, as well equally newspaper and magazine accounts and interviews, contributed material to the ... plot."[46]

In 1853, Stowe published A Fundamental to Uncle Tom's Cabin. This was to show the people who had criticized the novel's description of slavery that it was truthful. In the book, Stowe writes about the important characters in Uncle Tom's Cabin and near people in real life who were like them. Through this book, she writes a more "aggressive set on on slavery in the South than the novel itself had".[14] Like the novel, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin was also a best-seller. Nevertheless, many of the works in A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin was read past Stowe after she published her novel.[14]

Fifty-fifty though at that place were such criticisms, the novel was nonetheless very popular. Stowe's son says that when Abraham Lincoln met her in 1862 Lincoln said, "So this is the little lady who started this great state of war."[1] Historians are not sure if Lincoln really said this or not. In a letter of the alphabet that Stowe wrote to her husband a few hours after coming together with Lincoln, she does non say anything about this judgement.[47] After this, many writers have said that this novel helped make the North aroused at slavery and at the Fugitive Slave Constabulary.[47] It profoundly helped the abolitionist movement.[seven] Union general and pol James Baird Weaver said that the book made him assist in the abolitionist movement.[48]

Uncle Tom's Motel also interested many people in England. The first London edition came out in May 1852.[42] It sold 200,000 copies.[42] Some of this interest was because at that fourth dimension the British people did not similar the United states. A writer said, "The evil passions which 'Uncle Tom' gratified in England were non hatred or vengeance [of slavery], but national jealousy and national vanity. We take long been smarting (pain) under the conceit of America – we are tired of hearing her boast that she is the freest and the most enlightened land that the earth has ever seen. Our clergy hate her voluntary system – our Tories detest her democrats – our Whigs detest her ... All parties hailed Mrs. Stowe equally a revolter from the enemy."[49] Charles Francis Adams, the American minister to Britain during the war, said later that, "Uncle Tom's Motel; or Life among the Lowly, published in 1852, influenced the world more than quickly, powerfully, and dramatically than any other volume ever printed."[l]

Uncle Tom's Cabin was published in Russia at the end of 1857 and was soon recognized as a archetype of world literature.[51] Many people saw a very strong link between the globe of Uncle Tom's Cabin and the serfdom that still existed in Russia in 1850s.[51] In his letter to an abolitionist Maria Weston Chapman, Nikolay Turgenev wrote, "Many of the scenes described in the book seem similar an verbal delineation of equally frightful scenes in Russian federation."[51] Uncle Tom'due south Cabin served as an educational tool for Russian and Russo-Soviet elite in the mail emancipation period, and it also became part of Soviet children literature.[51]

The book has been translated into almost every language. For instance, it was translated into Chinese. Its translator Lin Shu made this the first Chinese translation of an American novel. It was as well translated into Amharic. Its 1930 translation was fabricated to assist Ethiopia end the suffering of blacks in that nation.[52] The book was read by so many people that Sigmund Freud believed that some of his patients had been influenced by reading well-nigh the whipping of slaves in Uncle Tom's Motel.[53]

Literary importance and criticism [modify | change source]

Uncle Tom's Cabin was the first widely read political novel in the United States.[54] It profoundly influenced American literature and protestation literature. Some later books that were greatly influenced by Uncle Tom'due south Cabin are The Jungle by Upton Sinclair and Silent Spring past Rachel Carson.[55]

However, even though Uncle Tom's Cabin was very important, many people thought the book was a mix of "children's fable and propaganda".[56] Many critics called the book "merely (only) a sentimental novel".[38] George Whicher wrote in his Literary History of the United States that "Nothing owing to Mrs. Stowe or her handiwork can account for the novel's enormous (great) vogue (popularity); its author'south resource ... of Sunday-school fiction were not remarkable ... melodrama, humour, and desolation … compounded (made upwardly) her volume."[40]

Other critics, though, have praised the novel. Edmund Wilson said that "To expose oneself in maturity (when ane has grown up) to Uncle Tom's Motel may … evidence a startling (surprising) experience."[56] Jane Tompkins said that the novel is one of the classics of American literature. She suggested that literary critics think badly of the book because it was only too popular when information technology came out.[twoscore]

Through the years, people have wondered what Stowe was trying to say with the novel. Some of her themes tin can be seen hands, like the evil of slavery. However, some themes are harder to run into. For example, Stowe was a Christian and active abolitionist, and put lots of her religious beliefs in her book.[57] Some accept said that Stowe wrote in her novel what she thought was a solution to the problem that worried many people who did not like slavery. This problem was: was doing things that were not immune justified if they did it to fight evil? Was it right to use violence to stop the violence of slavery? Was breaking laws that helped slavery right? Which of Stowe'due south characters should be followed: the patient Uncle Tom or the defiant George Harris?[58] Stowe thought that God's will would exist followed if each (every) person sincerely (truly) examined his principles and acted on (followed) them.[58]

People take too thought Uncle Tom's Cabin expressed the ideas of the Free Volition Movement.[59] In this thought, the character of George Harris symbolizes the complimentary labor. The complex character of Ophelia shows the Northerners who allowed slavery, even though they did non like it. Dinah is very different from Ophelia. She acts past passion. In the book, Ophelia changes. Like Ophelia, the Republican Political party (three years after) declared that the North must change itself. It said that the Northward must stop slavery actively.[59]

Feminist theory can as well be seen in Stowe'southward volume. The novel can be seen as criticizing slavery'due south patriarchal nature.[60] For Stowe, families were related by claret, not by family-like relations between masters and slaves. Stowe too saw the nation as a bigger "family unit". And then, the feelings of nationality came from sharing the same race. Because of this, she supported the idea that freed slaves should live together in a colony.

The volume has too been seen every bit trying to evidence that masculinity was important in stopping slavery.[61] Abolitionists began to modify the way they thought of violent men. They wanted men to help finish slavery without hurting their cocky-image or their position in lodge. Because of this, some abolitionists followed some of the principles of women'south suffrage, peace, and Christianity. They praised men for helping, working together, and having mercy. Other abolitionists were more traditional: they wanted men to act more forcefully. All the men in Stowe's book show either patient men or traditional men.[61]

Creation and popularization of stereotypes [modify | change source]

Illustration of Sam from the 1888 "New Edition" of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The character of Sam helped make the stereotype of the lazy, carefree "happy darky."

Recently, some people take begun criticizing the book for what they idea were racist descriptions of the book's black characters. They criticized the way Stowe wrote nigh the characters' looks, speech, beliefs, and the passive nature of Uncle Tom.[62] The volume's use of common stereotypes about African Americans[viii] is of import because Uncle Tom's Motel was the all-time-selling novel in the earth in the 19th century.[6] Because of this, the book (together with images in the book[63] and related stage productions) helped make a great number of people take such stereotypes.[62]

Among the African-American stereotypes in Uncle Tom'south Motel are:[10]

- The "happy darky" (in the lazy, carefree character of Sam);

- The calorie-free-skinned tragic mulatto (in the characters of Eliza, Cassy, and Emmeline);

- The loving, dark-skinned female person mammy (through several characters, including Mammy, a cook at the St. Clare plantation).

- The Pickaninny stereotype of black children (in the character of Topsy);

- The Uncle Tom, or African American who wants to please white people too much (in the character of Uncle Tom). Stowe wanted Tom to be a "noble hero". The stereotype of him was because of "Tom Shows," which Stowe could not stop.[17]

These stereotypes made many people recollect much more lightly of the historical importance of Uncle Tom's Cabin every bit a "vital antislavery tool."[ten] This change in the way people looked at Uncle Tom's Cabin began in an essay by James Baldwin. This essay was titled "Everybody's Protest Novel." In the essay, Baldwin called Uncle Tom's Cabin a "very bad novel".[64] He said it was not well-written.[64]

In the 1960s and '70s, the Black Power and Black Arts Movements strongly criticized the book. They said that the character of Uncle Tom was a function of "race betrayal". They said that Tom made slaves expect worse than slave owners.[64] Criticisms of the other stereotypes in the book also increased during this time.

All the same, people such as Henry Louis Gates Jr. have begun studying Uncle Tom's Cabin over again. He says that the book is a "primal document in American race relations and a significant (important) moral and political exploration of the character of those relations."[64]

References [modify | change source]

- ↑ ane.0 1.1 Charles Edward Stowe, Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Story of Her Life (1911) p. 203.

- ↑ 2.0 2.i ii.2 2.3 ii.4 two.5 Douglas, Ann (1981). Introduction [to Uncle Tom's Cabin]: The Art of Controversy. Viking Penguin Inc. ISBN0-14-039003-0.

- ↑ The Complete Idiot's Guide to American Literature past Laurie E. Rozakis, Alpha Books, 1999, page 125, where it says that one of the book's main letters is that "The slavery crunch can only be resolved (fixed, solved) by Christian honey."

- ↑ Domestic Abolitionism and Juvenile Literature, 1830–1865 by Deborah C. de Rosa, SUNY Press, 2003, page 121, where the book quotes Jane Tompkins on how Stowe's strategy with the novel was to stop slavery through the "saving power of Christian love." This quote is from "Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Politics of Literary History" Archived 2007-12-16 at the Wayback Machine by Jane Tompkins, from In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Piece of work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. New York: Oxford Upwards, 1985. Pp. 122–146. In that essay, Tompkins likewise says "Stowe conceived her volume every bit an instrument for bringing about the day when the globe would be ruled non by forcefulness, merely by Christian dear."

- ↑ "The Sentimental Novel: The Example of Harriet Beecher Stowe" by Gail K. Smith, The Cambridge Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Women's Writing by Dale Thousand. Bauer and Philip Gould, Cambridge University Press, 2001, page 221.

- ↑ six.0 6.ane Introduction to Uncle Tom'south Cabin Study Guide, BookRags.com. Retrieved May 16, 2006.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Goldner, Ellen J. "Arguing with Pictures: Race, Class and the Formation of Popular Abolition Through Uncle Tom's Cabin." Journal of American & Comparative Cultures 2001 24(1–2): 71–84. ISSN 1537-4726 Fulltext: online at Ebsco.

- ↑ eight.0 8.1 Hulser, Kathleen. "Reading Uncle Tom's Image: From Anti-slavery Hero to Racial Insult." New-York Periodical of American History 2003 65(1): 75–79. ISSN 1551-5486.

- ↑ 9.0 9.ane Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1986). Uncle Tom'south Cabin; or, Life Amidst the Lowly. 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN0-xiv-039003-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ 10.0 10.one 10.2 Africana: arts and letters: an A-to-Z reference of writers, musicians, and artists of the African American Feel by Henry Louis Gates, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Running Press, 2005, page 544.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 eleven.ii 11.three 11.iv Stobaugh, James P. (2005). Skills for Literary Analysis. Nashville, Tennessee: Broadman & Holman Publishers. ISBN0-8054-5897-two.

- ↑ Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin 1853, page 42, in which Stowe states "A last instance parallel with that of Uncle Tom is to exist institute in the published memoirs of the venerable Josiah Henson…" An extract of this information and acknowledgement is also in A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, pages 25–26.

- ↑ Weld, Theodore Dwight. Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001–2005. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ↑ fourteen.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 A Cardinal to Uncle Tom'southward Cabin, Uncle Tom's Cabin and American Civilization, a Multi-Media Archive. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ↑ Start Edition Illustrations, Uncle Tom's Motel and American Culture, a Multi-Media Annal. Retrieved Apr eighteen, 2007.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 xvi.02 16.03 16.04 xvi.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 xvi.11 16.12 xvi.13 sixteen.14 xvi.15 16.16 16.17 Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1986). Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Amid the Lowly. 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England: Penguin Classics. ISBN0-fourteen-039003-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ 17.0 17.1 A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Motel by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, page 31.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.ii 18.three xviii.4 SparkNotes Editors. "SparkNote on Uncle Tom's Cabin." SparkNotes LLC. 2002. http://world wide web.sparknotes.com/lit/uncletom/ (accessed March 18, 2010).

- ↑ Hagedorn, Ann. Across The River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad. Simon & Schuster, 2002, pp. 135–139.

- ↑ The Discussion Detective, issue of May 20, 2003, accessed February 16, 2007.

- ↑ Homelessness in American Literature: Romanticism, Realism, and Testimony past John Allen, Routledge, 2004, folio 24, where information technology states in regards to Uncle Tom's Cabin that "Stowe held specific beliefs about the 'evils' of slavery and the role of Americans in resisting it." The book then quotes Ann Douglas describing how Stowe saw slavery as a sin.

- ↑ Fatigued With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War by James Munro McPherson, Oxford University Printing, 1997, folio 30.

- ↑ Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Ceremonious State of war by James Munro McPherson, Oxford University Press, 1997, folio 29.

- ↑ "Stowe's Dream of the Mother-Savior: Uncle Tom'southward Cabin and American Women Writers Before the 1920s" by Elizabeth Ammons, New Essays on Uncle Tom'due south Cabin, Eric J. Sundquist, editor, Cambridge University Printing, 1986, page 159.

- ↑ Whitewashing Uncle Tom's Cabin: Nineteenth-Century Women Novelists Respond to Stowe by Joy Jordan-Lake, Vanderbilt University Printing, 2005, page 61.

- ↑ Somatic Fictions: imagining illness in Victorian civilization by Athena Vrettos, Stanford University Printing, 1995, page 101.

- ↑ The Stowe Debate: Rhetorical Strategies in Uncle Tom's Motel by Mason I. (jr.) Lowance, Ellen E. Westbrook, C. De Prospo, R., Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1994, page 132.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Women's Education in the United states by Linda Eisenmann, Greenwood Press, 1998, page three.

- ↑ The Company of the Artistic: A Christian Reader'south Guide to Great Literature and Its Themes by David 50. Larsen, Kregel Publications, 2000, pages 386–387.

- ↑ The Visitor of the Artistic: A Christian Reader'southward Guide to Great Literature and Its Themes past David L. Larsen, Kregel Publications, 2000, page 387.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of American Literature by Sacvan Bercovitch and Cyrus R. K. Patell, Cambridge Academy Printing, 1994, page 119.

- ↑ Marianne Noble, "The Ecstasies of Sentimental Wounding In Uncle Tom's Cabin," from A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe'due south Uncle Tom'due south Cabin Edited by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, folio 58.

- ↑ "Domestic or Sentimental Fiction, 1820–1865" American Literature Sites, Washington State University. Retrieved Apr 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Uncle Tom's Cabin," The Kansas Territorial Feel. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ↑ Reading Women: Literary Figures and Cultural Icons from the Victorian Historic period to the Present past Janet Badia and Jennifer Phegley, University of Toronto Press, 2005, page 67.

- ↑ 36.0 36.i Reading Women: Literary Figures and Cultural Icons from the Victorian Age to the Present by Janet Badia and Jennifer Phegley, Academy of Toronto Press, 2005, page 66.

- ↑ 37.0 37.ane A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Harriet Beecher Stowe'south Uncle Tom'south Cabin by Debra J. Rosenthal, Routledge, 2003, page 42.

- ↑ 38.0 38.one "Review of The Building of Uncle Tom'south Cabin by E. Bruce Kirkham" by Thomas F. Gossett, American Literature, Vol. fifty, No. 1 (March, 1978), pp. 123–124.

- ↑ "The Origins of Uncle Tom's Motel" by Charles Nichols, The Phylon Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 3 (third Qtr., 1958), folio 328.

- ↑ 40.0 40.ane forty.2 xl.3 "Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom's Motel and the Politics of Literary History" Archived 2007-12-16 at the Wayback Machine by Jane Tompkins, from In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. New York: Oxford UP, 1985. Pp. 122–146.

- ↑ "Uncle Tom'due south Cabin and the Matter of Influence" Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2010-03-17 .

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.iii 42.iv Slave narratives and Uncle Tom's Motel, Africans in America, PBS, accessed February sixteen, 2007.

- ↑ "Simms's Review of Uncle Tom'south Cabin" by Charles S. Watson, American Literature, Vol. 48, No. 3 (November, 1976), pp. 365–368

- ↑ "Over and higher up … There Broods a Portentous Shadow,—The Shadow of Police force: Harriet Beecher Stowe's Critique of Slave Police force in Uncle Tom's Motel" past Alfred L. Brophy, Journal of Constabulary and Organized religion, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1995–1996), pp. 457–506.

- ↑ "Woodcraft: Simms's Start Answer to Uncle Tom's Cabin" past Joseph V. Ridgely, American Literature, Vol. 31, No. 4 (January, 1960), pp. 421–433.

- ↑ The Classic Text: Harriett Beecher Stowe. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Library. Special collection page on traditions and interpretations of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Uncle Tom's Cabin, introduction by Amanda Claybaugh, Barnes and Noble Classics, New York, 2003, page xvii.

- ↑ "Review of James Baird Weaver past Fred Emory Haynes" by A. M. Arnett, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 1 (March, 1920), pp. 154–157; and profile of James Baird Weaver Archived 2007-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, accessed Feb 17, 2007.

- ↑ Nassau Senior, quoted in Ephraim Douglass Adams, Great Uk and the American Civil War (1958) p: 33.

- ↑ Charles Francis Adams, Trans-Atlantic Historical Solidarity: Lectures Delivered before the University of Oxford in Easter and Trinity Terms, 1913. 1913. p. 79

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.iii Mackay, John (2013). The Songs of Freedom: Uncle Tom'south Motel in Russian Civilisation and Guild. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Printing. ISBN9780299292935.

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst, Economical History of Ethiopia (Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie I University Printing, 1968), p. 122.

- ↑ Ian Gibson, The English Vice: Chirapsia, Sex and Shame in Victorian England and After (1978)

- ↑ Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. See chapter five, "Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Politics of Literary History."

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to Harriet Beecher Stowe by Cindy Weinstein, Cambridge University Press, 2004, page 13.

- ↑ 56.0 56.i "Uncle Tom'south Shadow" Archived 2010-02-04 at the Wayback Automobile by Darryl Lorenzo Wellington, The Nation, December 25, 2006.

- ↑ Smylie, James H. "Uncle Tom's Cabin Revisited: the Bible, the Romantic Imagination, and the Sympathies of Christ." American Presbyterians 1995 73(three): 165–175. ISSN 0886-5159.

- ↑ 58.0 58.ane Bellin, Joshua D. "Up to Heaven's Gate, down in Earth's Dust: the Politics of Judgment in Uncle Tom'southward Cabin" American Literature 1993 65(2): 275–295. ISSN 0002-9831 Fulltext online at Jstor and Ebsco.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Grant, David. "Uncle Tom'south Cabin and the Triumph of Republican Rhetoric." New England Quarterly 1998 71(3): 429–448. ISSN 0028-4866 Fulltext online at Jstor.

- ↑ Riss, Arthur. "Racial Essentialism and Family unit Values in Uncle Tom's Cabin." American Quarterly 1994 46(4): 513–544. ISSN 0003-0678 Fulltext in JSTOR.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Wolff, Cynthia Griffin. "Masculinity in Uncle Tom's Cabin," American Quarterly 1995 47(four): 595–618. ISSN 0003-0678. Fulltext online at JSTOR.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Smith; Jessie Carney; Images of Blacks in American Civilization: A Reference Guide to Information Sources Greenwood Press. 1988.

- ↑ Illustrations, Uncle Tom'southward Motel and American Culture, a Multi-Media Archive. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.two 64.three "Digging Through the Literary Anthropology of Stowe'south Uncle Tom", by Edward Rothstein, from the New York Times, October 23, 2006.

Other websites [change | change source]

-

Media related to Uncle Tom's Cabin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Uncle Tom's Cabin at Wikimedia Commons - Uncle Tom's cabin: or Life amongst the lowly Archived 2006-09-11 at the Wayback Auto; frontispiece by John Gilbert; ornamental title-page past Phiz; and 130 engravings on forest by Matthew Urlwin Sears, 1853 (a searchable facsimile at the Academy of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF Archived 2009-05-09 at the Wayback Motorcar format)

- Pictures and stories from Uncle Tom's cabin Archived 2006-09-11 at the Wayback Auto; "The purpose of the editor of this picayune work, has been to accommodate it for the juvenile family circle. The verses accept accordingly been written by the authoress for the chapters of the youngest readers …" 1853 (a searchable facsimile at the Academy of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF Archived 2009-07-03 at the Wayback Machine format)

- Uncle Tom's Motel at Project Gutenberg

- Uncle Tom's Cabin, available at Internet Archive. Scanned, illustrated original editions.

- Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site

- Free audiobook of Uncle Tom's Motel at Librivox

- More than on the lack of international copyright

Source: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncle_Tom%27s_Cabin

Comments

Post a Comment